In the summer you can always wake me up for a trip to Sigri. There’s delicious food and a cozy village beach on the dazzling blue bay, along with numerous long sandy beachesthat stretch out beyond the picturesque village. The only beach cafe you will find there is at Faneromeni (Etsi), the other beaches are at most disturbed by bunches of screaming seagulls. Etsi, managed by Nondas, is in a totally deserted landscape between large fields and some low sand dunes that temper the foaming waves. The impressive emptiness and the seldom quiet sea give the utmost feeling of serenity. Nondas serves only coffee, alcoholic drinks and toast, unless you make a reservation and arrange to have Nondas’ mother cook for you. Having lunch in this quietness is a dream. At least for me.

The winter is the perfect period for making wild plans to attract tourists to the island. This winter Sigri has not slept, but bubbled with energy. There even was a Christmas committee and now they are brainstorming how they can make Sigri attractive for tourists. But then they have to find the egg of Colombus (a Dutch expression meaning to find something nearly impossible).

There are rumours that the biggest public attraction of Sigri, the interesting Natural History Museum of the Petrified Forest of Lesvos, will be closed this summer due to rebuilding. During the making of the new road from Kalloni to Sigri, so many petrified trees popped up that expansion is necessary. The commission for luring tourists to Sigri will not be happy with that news, because the castle was to be restored by now — but isn’t; similarly the new harbour is not finished, nor is the hamam renovated.

In ancient times villages arose around water sources. As in the hills above Faneromeni, where Paleochori was founded, embraced by the walls of a castle. Lesvos used to have lots of castles, but when the Ottomans conquered the island in 1462, many of them were destroyed, as was the castle of Paleochori. The Ottomans settled in Sigri because of the natural and protected harbour. In 1746 Sultan Mehmet had a new castle built, its dilapidated walls now wavering but standing. Maybe the Ottomans also thought the village to be too quiet: around 1750 all inhabitants of Paleochori were forced to move to Sigri. And because there was laundry to be done in a village, the Sultan had made ceramic pipe lines transporting water from the source in Paleochori to a cistern in Sigri, equal to any Roman engineering work. From this reservoir water lines ran to the harbour so that ships could load up with fresh water and another line went to a hamam nearby.

Little remains in Paleochori, while in Sigri there are remnants of the cistern and some parts of the pipe lines, with branches to different fountains that still adorne some streets. In 1870 it was thought necessary to build a mosque upon the water reservoir. After Lesvos freed itself from the Ottoman empire they tore down the minaret in 1923 and converted the mosque into a church. This is the Agia Triada, still standing proud to the winds.

I do not know how this church alone, along with its hidden cistern, the idyllic white little houses and the sparkling bay with its animated village beach, can attract tourists. Nondas does know. For the coming summer he has engaged a cook to make Etsi into a real taverna.

The past can be thrilling, but we also have to look at the future: a new harbour, a bigger museum. Sigri has another island scoop: beer! Last year young entrepreneurs began to brew a great nomad beer: the blond Nissiopi and the dark Sedusa. Not having their own brewery, the Sigrian recipe was brewed elsewhere, but the nice bottles sold well, in part because I (not a beer drinker) drank just a little part of their stock — so tasty this Sigri beer is.

A brewery cannot be made in a few months, especially when there are still sponsors needed. But I am pretty sure that by the summer of 2021 it will be possible to visit a small brewery in Sigri, after having admired the new port and new items in the museum. And even the dust of your journey might be washed off in the restored hamam.

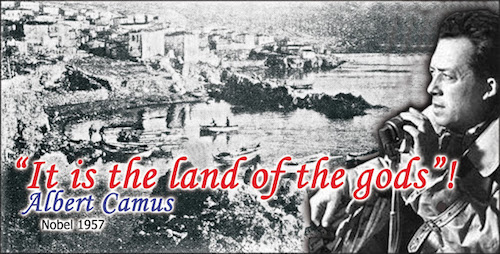

There is also the story of the well known French writer Albert Camus (1913 – 1960) who spent some time in lovely Sigri and was so impressed by the friendly village and its surroundings that he was willing to die there. But a year after leaving fate had him die in a car crash in France, so he never came back and Sigri never became the village of Camus.

If you want to enjoy the village just like Camus did, there is only one summer left to do so, before Sigri turns into one of those places where masses of tourists come to take a selfie at sunset. Because wherever you are in Sigri, seeing the sun plunge into the sea remains a breath taking event.