It is difficult to say which trees are in the majority on the island of Lesvos: olive trees or pine trees. The value of the olive is obvious to everybody, but what pine trees give (except their cooling shade during hot days) is an old story that not everybody knows.

The fruit of the pine is the cone and the seeds that are hidden between the plates of each cone are edible. However, they are often so small that nobody bothers to harvest them, except for the fruit of the Stone (or Umbrella) Pine which has seeds big enough to collect (and sell) for consumption as pine nuts.

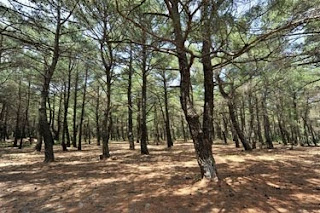

It is a pity that Lesvos is not full of these Stone Pines, otherwise their nuts would have found a place in the Lesvorian kitchen. The trees that cover the middle of the island around Mt Olympos are Aleppo Pines (Pinus Halepensis), although scientists say it is a subspecies or perhaps even quite a different pine: the Turkish Pine (Pinus bruta). In the west of the island you can also find Black pines (Pinus negra).

Pine trees provide wood, although it is not hardwood but in Lesvos, unlike the Amazon region, wood lumbering is practised with sustainable techniques and it seems clear that people here realize how important the island’s pine forests are to the environment.

They also are part of Lesvorian history. During the Turkish occupation wood and also resin were taken from pine trees. A by-product of resin is tar, an ideal material for waterproofing wooden ships.

Until the big ‘exchange’ between Turkish and Greek population in 1923, nomads called Giourouks used to live in the woods around Agiasos. They lived in tents and made a living selling firewood and other wood products.

From the Twenties on forests were rented to companies to harvest the resin. They hired local workers who were glad to get a job because there was a lot of poverty in those days.

Sometimes you may still see a little square bucket hanging on a tree trunk. The period when the resin trade boomed was from the Twenties to the mid Sixties and then it suddenly stopped. It was not because the trees had been over used or worn out, but because there were no workers left. People on Lesvos got tired of living off the land and the poverty of life in Greece and they emigrated in big numbers for cities on the mainland or to South-Africa, South-America, Australia or the United States.

Half a century ago life was quite different in mountain villages like Ampeliko. From April to October many people inhabited the pine forests and collected resin, six or seven days a week. And even when they ate spoiled food or drank bad water, they managed to keep themselves and their families alive. They lived in small huts, made of low stone or wooden walls, with roofs made from tree branches, and beds from the soft pine planks hewn from the trees. For a door they might have nothing more than a piece of cloth hanging across the hut’s entrance.

As now there were policies regulating the harvesting of trees and the collection of resin, which could only be done by people who knew the skills. They used a special wood cutting tool known as an ‘adze’ and when you made a good cut, the veins through which the resin in the trees flows, did not close but stayed open. The cut had to be of a certain height and depth, otherwise the tree would be damaged, and anyone making the wrong kind of cut had to pay a penalty! The cut itself is named ‘the face’ and after the first cut, there are two more which scrape off a layer of the face to open new veins of resin.

Because of the years of emigration most small mountain villages now have very small populations, and even when people still lived there the villages were often empty because people were either away collecting resin or, in winter, working in the olive groves.

The Greek moviemaker Irini Stathi has made a documentary about a group of old villagers from Ambeliko: The Face of the Pine Trees. It is a valuable record of a way of life that is in danger of being forgotten.

In it old people tell their stories about working for the resin and how the forests were rented out and every worker was allocated trees, according to their ability. A woman tells how a supervisor took away her adze because she had made a wrong cut and she had to beg him to give it back, asking him to make her pay a fine instead of taking away her working tool so she could continue to make a living. Others recall that during the civil war guerrillas lived in the woods, but they were to be more afraid of the soldiers. Everyone in the film agrees: it were hard times, but they were happy then, whereas now, although the terrible poverty has gone, everybody is complaining. One old grandmother remembers how the mountains used be full of the sound of music, because when the resin workers started their day they sang, and again when they finished. An old man adds: “Now even the birds don’t sing anymore”…

The collected resin was brought on a donkey to Megalo Limni, later on to Achladeri and even to Panagiouda (besides Mytlini) to be transported by boat to different factories. At many a place in the forests you will still find traces of this life: old huts, tanks where the resin was collected and even an old taverna!

The most well known product of pine resin is of course retsina, a wine made for thousands of years, which matures in wooden barrels that are rubbed with resin. Nowadays more alternative (and better) wines are available on the Greek market and they threat to take over from the traditional resinated wine. More and more people now seem to dislike drinking retsina but they are wrong. I do not think that the days of the singing woods when the pine tree had a face will come back, but a tasty glass of retsina is just as essential to Greek life as feta and should not be missed.

*Irini Stathi wrote a number of books and publications about Greek movies, she edited an amount of movie productions and she worked some 10 years for the great, Greek film director Theo Angelopoulos. Nowadays she works as an assistent professor at the Aegean University at the department of Cultural Technology and Communication.