Imagine that you find on old grave and you open it to do some research and you discover a skeleton that has been hammered into its coffin with huge spikes! Not so long ago this happened to the American archaeologist Hector Williams of the University of British Columbia, who has been investigating relics around Mytilini. He found the grave in a nineteenth century Turkish cemetery near the city’s northern harbour.

It seems likely that people had buried a man who they feared might rise from the dead: one spike was hammered through his throat, another through his pelvis and a third through his ankle. And to be sure heavy stones were placed on the coffin lid.

The find blew a gust of excitement through the scientific world, made all the more mysterious with the discovery of another grave close to a little Taxiarchis church just above Mytilini. Here the same enormous spikes were found lying beside the skeleton. The find suggested that people thought they were burying a vampire and it inspired the film director Julian Thomas to make a television documentary (for the History Channel) about it. He called it Vampire Island. The poor spike-victim was called ‘Vlad’, after the Walachian ruler Vlad Tepes (1431-1476), aka Vlad Dracula or count Dracula.

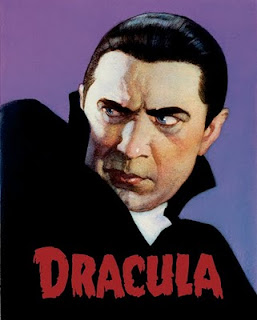

It was the Irish writer Bram Stoker who made vampires popular (and feared) in Western Europe with his book Dracula (1897), a fantasy about the blood guzzling count Dracula from Transylvania. Stories about vampires however are much older and every culture has mythical beings who rise from the dead to drink the blood of the living. In Greek culture they are the vrikolakes.

Belief in vampires is mainly caused by fear that the dead will come back from their graves to take revenge. There are enough creepy (and hilarious) movies which have scenes in which the dead suddenly stir from their coffins.

The TV documentary tried to explain this fear of the living dead by, for example, the chemical reactions that continue in a body after death – cause nails and hair keep growing for a while, gasses make the belly swell up and rigor mortis can cause limbs to make small movements.

In ancient times people who were different were often treated as outcasts. If they were physically or mentally ill people were afraid they could change into a vampire after death – especially people suffering from tuberculosis (who give up blood when they are very ill). But what of our Vlad? Scientist researching his skeleton think he was a strong and healthy man, so he was probably an outcast for another reason.

Here in Greece people get buried a day after they die. They then stay in the ground for two years. Traditionally, the family would look after them for this time in the afterlife by bringing food, drink and some conversation. Nowadays the custom of leaving food and drinks at the grave has faded but as long as they are in their graves the dead can still expect plenty of company. At the end of the two years the remains are dug up by which time it is to be hoped all bones will have turned white. If they are not clean or they are black it means the person must have been a sinner and the family should be ashamed. The remains of such people have to be reburied and if after a second exhumation the bones are still not white, it means maybe the deceased was not even human and, who knows, might have even been a vampire.

However, science has proved that the colour of bones depends on the kind of soil they were buried in and anyway they can be washed white by a priest with wine and vinegar (which is another way of dealing with vampires). This way the family doesn’t have to be ashamed of the dead person’s reputation.

The English Archaeologist Charles Thomas Newton wrote a book about his time here on Lesvos, where he was vice consul in Mytilini from 1852 to 1855 – Travels and Discoveries in the Levant (1865). In it he said that in the sea near the coast of the capital there was a small island where anyone suspected of being a vampire was buried. Since people believed that vampires could not survive in salt water, if they did come back to life they could not escape from the island.

According to archaeologist Hector Williams, Newton was referring to an islet just across from Pamfila. Williams did not yet get the chance to dig around there, but from a plane he thought saw the remains of old buildings and he is sure that it was a place unique on earth – vampire island!

Just across from Crete is the island Spinalonga. For some years it has been a popular tourist destination but until the 1950s when a cure was found it was a leper colony. At that time not many people dared visit Spinalonga but these days lots of visitors fearlessly roam the island.

Hector Williams thinks Lesvos has a vampire cemetery just offshore. I hope he soon will dig up its graves to prove his theory. Who knows what atrocities the graves will reveal? It will give the myth of Dracula a Greek twist and could be a stimulus to tourism on Lesvos.