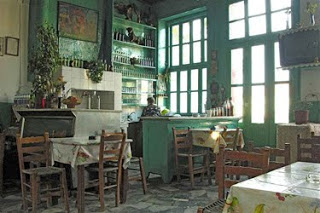

(Picture: a kafenion in Loutronpoli-Thermi)

You will not find the name Epicurus in a list of the best known Greek philosophers like Pythagorion, Socrates, Plato or Aristotle. Although he did found a school of philosophy — best described as the philosophy of happiness. Epicurus lived from 341 – 270 BC, and was born on the island of Samos and later established his teaching school in the garden of his home in Athens.

Epicurus looked for happiness, mental and physical happiness (ataraxia) as the state where all natural needs were satisfied and you were without any fears, or pain or punishment from the gods. However, he did not preach that you could find happiness over-indulging at a lengthy banquet where all the best food was served — a decadent tradition that the Romans later introduced. In fact the message from Epicurus was that enough is as good as a feast. Another element in his philosophy was that having many good friends would also make you happy.

So I can imagine that this Epicurean thinking would be a perfect philosophy for living on Lesvos. People here do eat well and simply and Lesvorians have many friends, you can tell if you notice how many drivers just stop in the middle of the road for a chat with a friend passing the other way. The moderate Lesvorian is happy and does not like to step out of line, another aspect of the Epicurean philosophy.

But the Lesvorians did not like Epicurus at all when he came to Mytilini to teach his philosophy. Most schools were under influence of Plato and Socrates. Epicurus thought Platonists were too much into reason and not interested enough in pursuing personal happiness. No-one knows what happened in the year 306 BC, but it’s a fact that Epicurus suddenly left the island in the middle of winter in a hurry – not a good time to travel. He himself said that that mobs were after him and he thought pirates were dangerous people. In other words, he probably got chased off the island because of his subversive ideas.

Judging by the way of life on the island now, however, it’s fair to say that, Epicurus would be happy to see that Lesvorians love the life they live and are close to that feeling of ataraxia. They have some food, a drink and live close to nature. Which brings us to that famous ‘Mediterranean diet’ of simple and fresh ingredients, with lots of vegetables and cereals. And for the Greeks, having dinner doesn’t just mean satisfying the appetite for food and drink, but to share company with friends. Eating is very much a social event. Greeks love to eat together — with as many people as possible.

A way to relieve hunger just a little is partake of the national drink. When you order an ouzo in a kafenion you also get some small plates of food: known as pikilia or mezèdes. A kafenion is mostly a badly illuminated space where a few old men take hours to sip their coffees. The traditional small restaurants (mostly illuminated by brighter tubular lighting) may also serve pikilia with the ouzo, even if you do not ask for it, but in modern restaurants ordering an ouzo means that they will bring you the menu as well and, of course, you are expected to order and pay extra for the dishes you eat.

When you want ouzo and pikilia you only have to order the ouzo, and the little snacks can be anything: a plate with some olives, a piece of bread and cheese but in most kafenions here on the island mama the cook will not be satisfied serving you just that, so she will get busy making something out of whatever she has in her kitchen — maybe a few small fish, fried aubergine or paprika, sausages, chickpeas, white beans or fava, fried potatoes, feta, hard goat cheese or ladotiri (goat cheese in oil) and whatever vegetables she has just picked from the land, or what a farmer or fisherman has brought by. And when you want to pay the few euro this will cost you, she will not be finished with her cooking but will seduce you with more dishes for that second glass of ouzo.

This winter we made it a habit when finishing a long walk to take an ouzo in such a picturesque kafenion. And at such places, for sure, we get that ataraxia-feeling. We rest our tired legs at kafenions hidden in the smallest village plaza’s where no tourists ever come. We look for the most traditional one and we are never disappointed. Even if we arrive at 4 or 5 PM – an hour at which any Greek is usually still in the middle of the siesta – we are always welcomed warmly, and the deep-frying oil will be heated, some chairs rearranged and, even in the sleepiest kafenion, the evening can begin.

However the Epicurean habit of enjoying simple food with a drink this way will die out altogether when those old kafenions close down and disappear. Modern cafes don’t have rudimentary (even shabby) little kitchens suitable for preparing tiny meals in the narrow space under the rows of dusty but colourful little bottles of ouzo. The younger generation don’t fancy putting effort into preparing the small dishes that are served with a drink. You might get a handful of peanuts or roasted almonds, with your ouzo, as with your whisky.

I do understand why youngsters don’t like these traditional kafenions where time seems to have stopped and where you only find the old folks, simmering at their table behind a paper, a coffee or an ouzo. But there will come a time that they will realize that together with these old kafenions a valuable and healthy tradition will have vanished. A kafenion is not only a safe heaven for old and lonely people but as well a place where you can pop in to satisfy a hunger or thirst and where the traditional dishes from grandma’s cooking pots are like angels on your tongue: a place where you can taste the essence of Epicurean happiness.

(It is good that many of these places already have been saved on film by the Lesvorian photographer Tzeli Hadjidimitriou in her book 39 Coffee houses and a barber’s shop (of Lesvos).