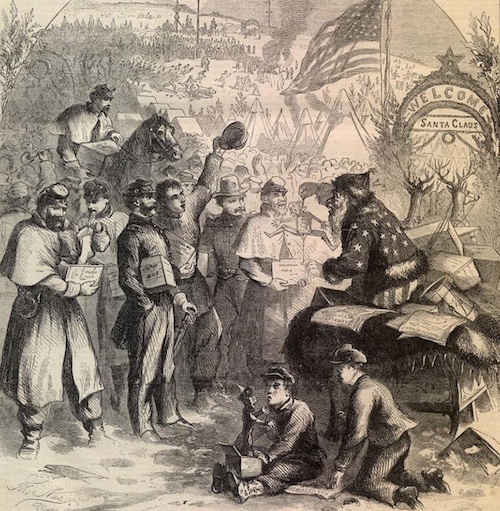

(Thomas Nast: Santa Claus in the civil war, 1863)

Saint Nicholas is the namesake of the Bishop of Myra, a holy man who lived at the beginning of the 4th century in Lycia (nowadays Turkey). Nicholas of Myra came from a rich Greek family and became a beloved priest. It was only after his death that plenty of stories arose about all the miracles he produced (like the resurrection of three children who were killed by a butcher.) He also once threw three pouches full of golden ducats into a house, where a poor family was trying to gather a dowry for each of their three daughters. In the Netherlands they now throw gingerbread nuts when celebrating Saint Nicholas’ name day on December 5th.

After a Greek couple ‘made’ Saint Nicholas, centuries later the Dutch were responsible for the birth of the Christmas man. Dutch colonists took their Saint Nicholas traditions all the way to America. There this Holy Man slowly transformed into Santa Claus and his celebration extended towards the days around Christmas. In 1821 a first illustrated Christmas poem was published: Old Santeclaus with Much Delight. It portrayed a man with a brown beard, a red coat, wearing a Russian style fur hat; his sleigh was pulled by a reindeer. Just like Saint Nicholas this new Claus rushed over the rooftops and through a wood of chimneys which he used to throw his presents down. It was the first time Santa Claus made his appearance on Christmas Eve. Two years later The New York Times published another Christmas poem: The Night Before Christmas, that introduced no less than eight reindeers: Dasher, Dancer, Prancer, Vixen, Comet, Cupid, Donner and Blitzen. Rudolph came later as the ninth reindeer.

Then the Christmas man’s image still had to take shape. Thomas Nast, cartoonist at the American Harper’s Weekly was in favor of abolition of slavery, civil rights and the Republicans and used Santa Claus in his caricatures. His first Christmas man, published in 1863 sat in his reindeer sleigh in opposition to soldiers of the civil war. He was dressed in the stars and stripes of the American flag. In his hands dangled a puppet with a noose around his neck, its face looking amazingly like the then president Jefferson Davies. Eventually 33 Christmas man cartoons by Nast were published, the last one in 1886. By then Santa Claus finally looked like the man we see jumping through our Christmas Days: a merry man with a thick, round belly, his hair and beard white, dressed in a red costume, garnished with white fur edges.

Through Nast’s cartoons Santa Claus found a home at the North Pole, acquired a hall to make his presents and a thick book in which he wrote which children were naughty. Nast also drew inspiration from other traditions for his drawings, for instance the decorated fir tree from Germany: or putting a shoe at the hearth. That had been a Dutch tradition in the 15th century on the name day of Saint Nicholas: first shoes were put in the church where they were filled by rich people, the proceeds to be distributed amongst the poor children. Later the shoes were set near the chimney in the homes. In America the shoes were replaced by stockings.

Christmas doesn’t mean only merry days. In the dark, cold Christmas days the world is full with mythical, terrifying creatures, mostly men, who put naughty children into a sack to kidnap them or to eat them: from the Dutch Black Peter, the Swiss Schmützli, the West Cape Antjie Somers to the Haïtian Tonton Macoute. Charles Dickens’ creation Scrooge didn’t put the children into a bag, but didn’t want them to get any presents

In Greece you only have to watch out for a kind of gnome: Kallikantzari. In the days between Christmas and Epiphany they make the house unsafe with small bullying tactics. The men painted black and decorated with huge bells during the Carnival in Mesotopos (Lesvos) are a bit alike the Krampus who help Santa Claus in the Alps: centaur-like black devils who are dressed with rusty bells and chains. But then it is Carnival and nobody is afraid.

Now all those scary creatures have competition from the men thirsty for power, who not only frighten children, but the entire world population. During the First World War there were different Christmas truces, a time to recover a bit from all the atrocities. Nowadays a lot of money is spent to create a warm and light Christmas feeling but even Father Frost (Ded Moroz), the Santa Claus of Russia and Ukraine who presents gifts to children at New Years’ Eve, has been unable to use his magic stick to freeze the war. So many Santa Clauses, but peace seems further away than ever.